The Etymological and Medical Origins of Vaccination: The Conquest of Small Pox

Vintage Vaccination Poster

The history of small pox is a window into the history of civilization. The human virus causing the disease is thought to have emerged from a rodent host. It appeared in humans at least by 10,000 B.C.E., in the first agricultural settlements in North Africa. It was possibly spread by Egyptian merchants to India. The lesions of small pox have been found on Egyptian mummies from around 3000 to 1000 B.C.E. and described in ancient Chinese and Sanskrit texts of the same period. Small pox may have been introduced into Europe in about 600 A.D. The first evidence of the erosion of the Roman Empire was tied to large epidemics, estimated to have killed hundreds of thousands of persons. The disease was introduced into the Americas by conquistadors and decimated populations contributing to the demise of the Aztec and Inca empires. The slave trade also introduced the virus into the Caribbean and the Americas, since the disease was rampant in Africa. Australian indigenous peoples were also decimated when Europeans brought the disease to that island continent.

In the late 1700’s, an inquisitive and farsighted English physician, Edward Jenner, decided to act on the observation of milk maids that their development of cow pox, a mild, localized skin eruption, protected them from small pox. That human pox disease was raging throughout the world in periodic epidemics and becoming endemic in many places. Cow pox, also, was prevalent, as were other forms of animal pox, (e.g. swine pox), leading to hand lesions on milk maids, acquired from handling the udders of cows. Of course, at that time, it was not appreciated that the cause of the disease was a microorganism, specifically a virus.

Based on the conviction of milk maids that if they had had cow pox, a mild, self-limited local infection, they were protected from small pox, a scarring, disfiguring and lethal human infection (mortality rates averaged 30% of those infected), Jenner took the pus from the cow pox hand lesion of the milk maid Sarah Nelmes and applied it to a cut he induced on the skin of the arm of eight year old James Phipps. James was Jenner’s gardener’s son. He, later, repeatedly exposed young Phipps to the pus of small pox lesions and he did not get the human pox disease. Jenner went on to do the same thing to other persons, all of whom were, apparently, protected from the deadly small pox after their prior exposure to cow pox. Jenner’s paper submitted to the Royal Society describing the results of his experiment was rejected. In 1798, he published a monograph at his own expense entitled “An inquiry into the cause and effects of variolae vaccinae”. “Vacca” is the Latin term for cow. Variolae vaccinae is the Latin for “pustules from cows”. The term “vaccination” used as a noun was subsequently suggested to Jenner by a colleague to refer to the cow pox inoculation. Prevention of small pox by the inoculation of pus of a cow pox lesion was the first medical vaccination supported by a human clinical trial, albeit an imperfect one. It was akin to some modern vaccines: using an attenuated (weakened and non-infectious) microbe to prevent the infection by the more virulent form.

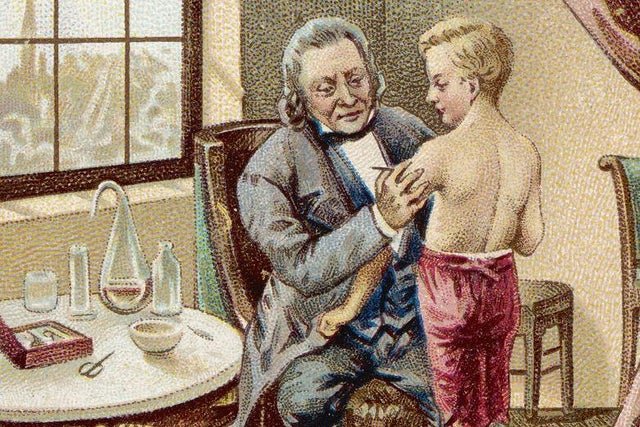

English Physician Edward Jenner giving the first successful Smallpox vaccination

If one was to pick one event that resulted in the greatest impact on the health of humankind, Jenner’s experiment and promulgation of vaccination would be a good choice. First, it led, 180 years later, to the eradication of small pox by the World Health Organization’s astounding world-wide program of vaccination, including in the most remote places in the world. Additionally, Jenner set the precedent that one could protect against a morbid or lethal infection by “vaccination” with a less virulent biologically related microbe.

Jenner’s work had been preceded by inoculation (later termed “variolation”), the use of the pus from an aged human small pox lesion to “inoculate” another person, in hopes that he or she would get a mild small pox infection and be spared the future ravages of the disease. This practice dates back at least to 16th century China and the technique spread to Africa, the Middle East and, eventually, in the late 18th century, the English colonies in North America, as described in the writings of Reverend Cotton Mather and considered a valuable approach by Thomas Jefferson. The inoculated individual developed fever, some pox lesions but, usually, recovered and was, henceforth, no longer susceptible to “the pox”. The British apparently used small pox contaminated items to infect Indian tribes (and perhaps, the French) they considered adversaries in North America. George Washington, who had recovered from a mild case, inoculated (variolated) colonial soldiers with small pox to prevent small pox from devastating his small army. Variolation, however, could produce severe disease and death, but its effects were orders of magnitude less severe than the natural disease, overall. Because of the devastating effects of small pox with mortality rates estimated to be as high as 50 percent in some epidemics, this approach was considered reasonable.

Donald A. Henderson (first man on left) as part of the CDC's smallpox eradication team in 1966. by Dr. John J. Witte/CDC

The eradication of small pox by a World Health Organization team led by Donald A. Henderson (1928-2016), a physician and epidemiologist, was perhaps the greatest single accomplishment in the annals of preventive medicine and at this writing a singular landmark, the eradication of a human disease that killed an estimated 300 million people in the 20th century and many millions before that time. It left communities devastated, families disrupted, children orphans, survivors grossly disfigured from facial scarring, in some cases blind, and commerce, communities and, indeed, civilizations destroyed. The eradication of small pox is the only example of such an achievement. It was made possible by vaccination.

Today, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lists 26 vaccines available for prevention or reduction in severity of infectious diseases. The effort to eradicate polio by vaccination was set back for a time; but, the World Health Organization has reenergized the effort and, if successful, it would become the second human disease of high consequence to be eliminated world-wide by vaccination following small pox; the last case in the world of the latter was reported in 1977. It was declared eradicated in 1980 about two centuries after Jenner’s introduction of vaccination.

The conquest of covid-19 is dependent on vaccination. The resistance to vaccination will prolong the epidemic and will prevent a return to full normalcy. In this situation, the quality of one’s medical care is secondary to the quality of one’s public health programs. The former will save lives but will not control the epidemic and allow restoration to normalcy. The hope that the virus will become less virulent has not been supported by the nature of the mutants that have evolved. They have been as or more transmissible than the earliest strain and just or even more virulent. Only the misguided reject vaccination. This results from a variable combination of ignorance, superstition, contrariness, and politicization.

Written November 2021